by Harold McGee, Retired Ethnologist.

During the summer of 1991, a Japanese friend and I made a tour of Hokkaido museums, galleries, historic sites and libraries. I was interested in cultural identity and the ways in which a people represent themselves and others through these institutions. Of particular interest was the portrayal of the Ainu by the Japanese and by themselves.

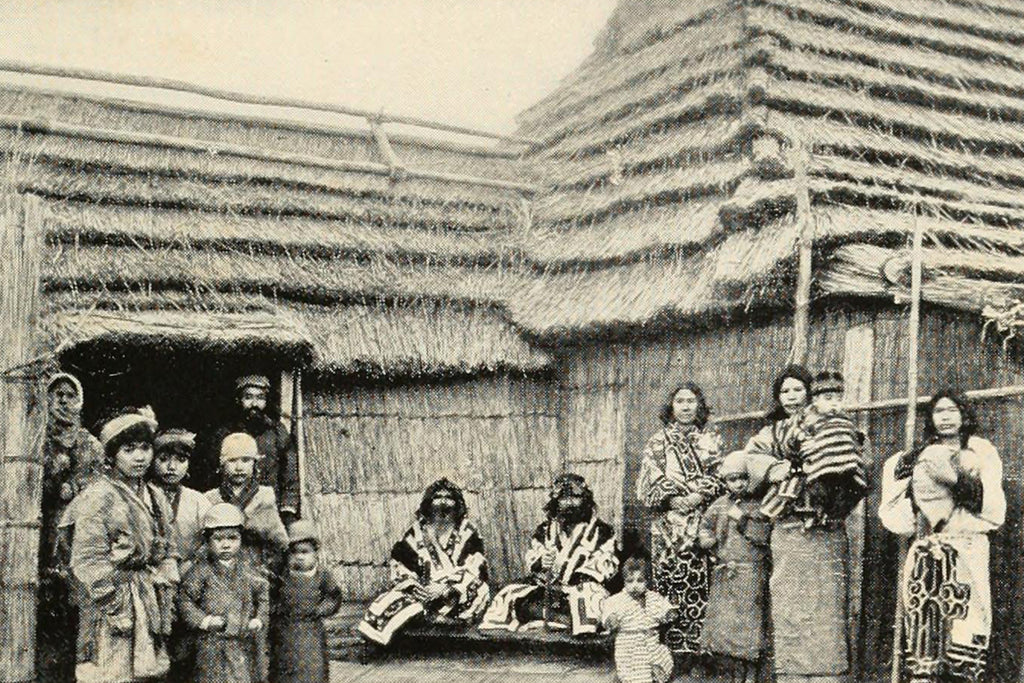

The Ainu are the indigenous people of north-eastern Japan and parts of Russia. For much of the historical period they occupied the Kurile Islands, the southern half of Sakhalin Island, and Hokkaido Island. They likely inhabited much of the Tohoku region of Honshu in the late prehistoric era. As the Yayoi Japanese expanded to the northeast and the Russians to the east, the Ainu were increasingly confined to Hokkaido. Archaeologically, their culture developed out of the Jomon Culture and their language is considered a linguistic isolate (not related to any other known language). The societies which developed from the Jomon are the Ainu to the north, the Ryukyus to the south, and the Japanese who mixed elements of Jomon and Yayoi cultures when Yayoi moved to the Japanese archipelago. The colonial expansion of the Yayoi Japanese, both north and south, with attempts to forcefully assimilate the Ainu and Ryukyu peoples resulted in the modern Japanese population.

A visit to the fabulous Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples in Abashiri, which represents cultures of all circumpolar preindustrial societies, reveals the similarities among adaptive economic strategies for life in this region while acknowledging differences in non-adaptive aspects of culture. The artefacts associated with fishing, hunting, gathering of plants, and food preservation are remarkably like those of peoples living in the Canadian sub-arctic. There are notable similarities in some expressive culture elements as well. For instance, there is a reverence for the bear as a powerful spirit being who links the world of human activity with that of the deities.

At a number of the reconstructed villages (kotan) throughout Hokkaido, traditional dances are performed for tourists. A powerfully moving dance was performed by about twenty women with an age range from mid-teens to the early elderly at the Ainu kotan at Akan. They formed two opposing lines and began to sway with their arms raised. As the dance progressed their loose hair began to sway and as the tempo increased they had been transformed from a dance troop into a dense forest being blown about by a hurricane. As the storm (and music) abated, they calmly left the performance space. The connection between humans and the forces of nature were made manifest.

In Asahikawa, at the Kawamura Kaneto Ainu Museum, an elderly woman with some facial tattoos approached us and began rubbing my forearm and speaking Japanese to my companion. Conscious public touching of another person is not something that often takes place in Japan. As she rubbed my arm, she said to my companion, “He is like our men used to be.” It should be noted that I also had a full beard at the time. In the past, the Ainu were sometimes described as “the hairy Ainu” because the men sported full beards and had a good deal of body hair; not a characteristic usually associated with Asian populations. However, two centuries of efforts to assimilate the Ainu into the general Japanese population resulted in intermarriage and this historic hairiness has been much reduced.

This assimilation in the early colonial period was characterised by land theft, forced labour, and forced marriages to Japanese. Discrimination by the militarily and economically dominant Japanese continued throughout the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth century. An adaptive strategy of many Ainu was to attempt to pass as “ordinary” (Yayoi) Japanese. The official estimate of the number of Japanese of Ainu heritage is 25,000; unofficial estimates suggest there may be as many as ten times that number. As among other indigenous peoples throughout the world, the Ainu have begun to regain control of their ethnic identity and to develop pride in the culture. There is a resurgence of the language and greater engagement in decision-making that affects their communities. So, as you enjoy your haskap powder, give a thought to the Ainu who included haskap berries in their traditional diet.